DIVING

by Robert Böddeker

Turning over stones

I’ve always thought of the ocean as a contradiction. It is vast but finite, inviting but unknowable, a space that offers both connection and separation. Growing up, the ocean wasn’t just a place; it was a feeling—a deep, wordless fascination that I couldn’t quite explain.

Every time I approached a body of water, I would crouch down, lift a rock, and look beneath. Sometimes there was nothing but empty sand. Sometimes I found crabs or tiny, alien-like creatures darting through the shadows. Either way, I was hooked. Now, as an adult, I wonder: Was this fascination with the ocean just the curiosity of a child, or does it reveal something deeper—something we’ve forgotten about ourselves? In the Anthropocene, the age of human dominance, we’re masters of the earth and conquerors of the seas. But that mastery feels hollow when I stare into the water, searching for a connection that remains elusive.

Oceanic Feeling

Writer Romain Rolland referred to the “oceanic feeling” in his correspondence with psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud as a profound sense of oneness with the universe, a connection that transcends boundaries. For me, the “oceanic feeling” is perhaps the best description I can associate with my lifelong fascination for the sea.

This project allowed me to explore that connection—or negotiate a position—with the ocean as both a subject for dialogue and a space of discovery. Rather than seeking answers, I aimed to observe without judgment, to explore what might seem at first sight banal and the overlooked: the small, unremarkable things that often get lost in the rush of daily life. Yet, the modern world doesn’t encourage such feelings. It teaches us to see the ocean not as a partner but as a resource—to extract fish, drill for oil, and discard waste.

The North Sea exemplifies this tension. It’s a place of awe-inspiring beauty shaped by wind and waves, but it’s also one of the most industrialised bodies of water on the planet. Beneath its surface liesa story of resilience and exploitation, of ecosystems reshaped by human ambition. I caught myself viewing my surroundings in the same way we often do—through the lens of utility, as if it’s the only way we know how to think as humans.

Four Media

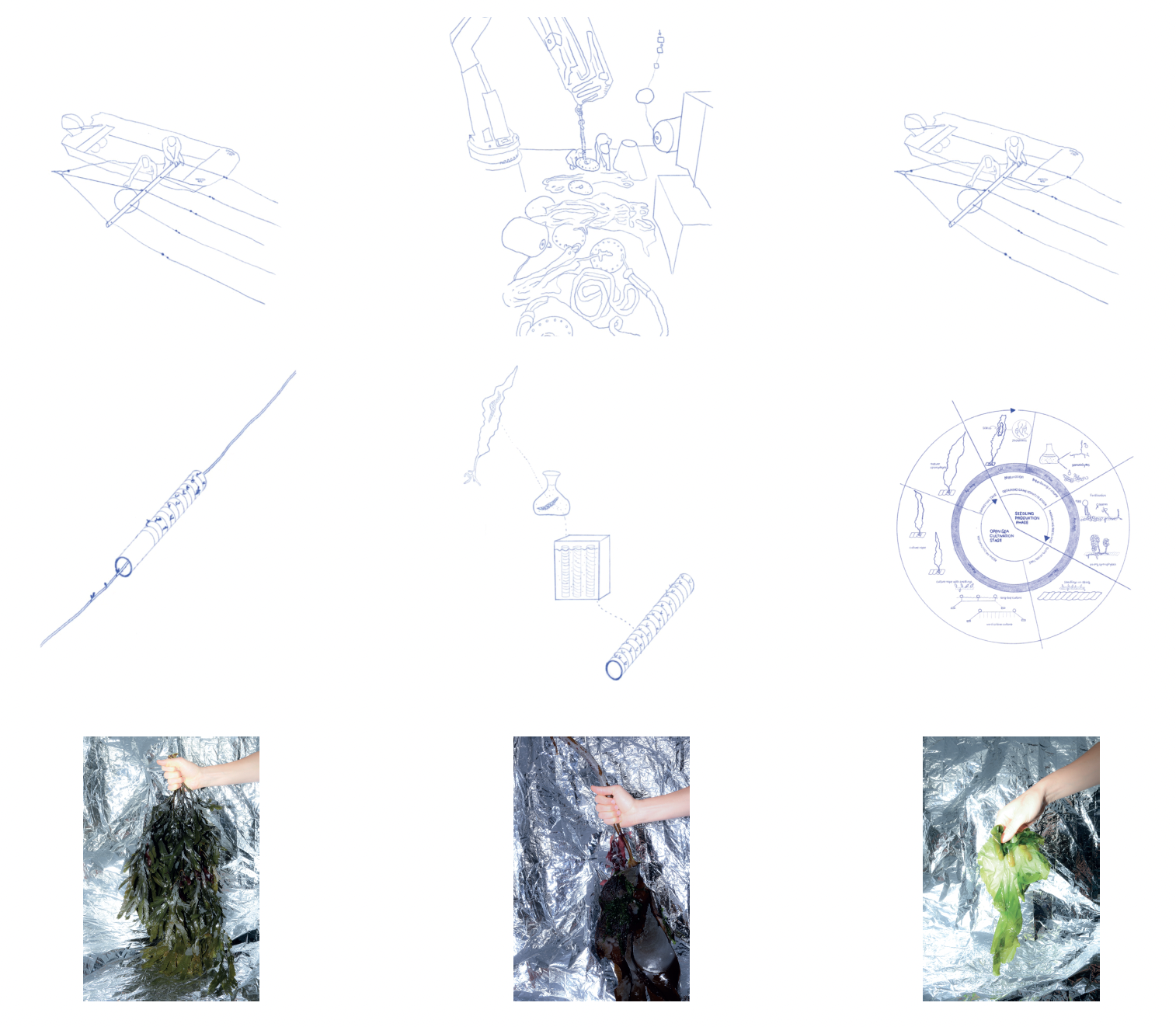

The journey to understanding the ocean has been like turning over stones—each one revealing a new perspective. These four “stones”, which are expressed through four distinct media, form the exhibition.

1. The Photo-book: Topography of the North Sea

2. The Projection: Breaking the Surface through the aquarium

3. The Lens of the Anthropocene: Seaweed farming

4. The Painting: Building a relationship

When I began this project, I approached the North Sea through a familiar lens—from the land, photographing Norway’s topography, the buildings along the shore, and following the water from mountains to sea. Finally, I turned to the ocean and broke through the surface with a flash to discover what lay beneath.

This approach, similar to how I’ve explored other landscapes, worked for a while. My curiosity pushed me forward, but I began to feel like an intruder—stepping into a realm that normally stays hidden. I soon realised that the ocean isn’t a landscape that can be frozen or fully understood from above. It is dynamic, boundary-less, and always floating. Despite my attempts, the sense of distance between us remained.

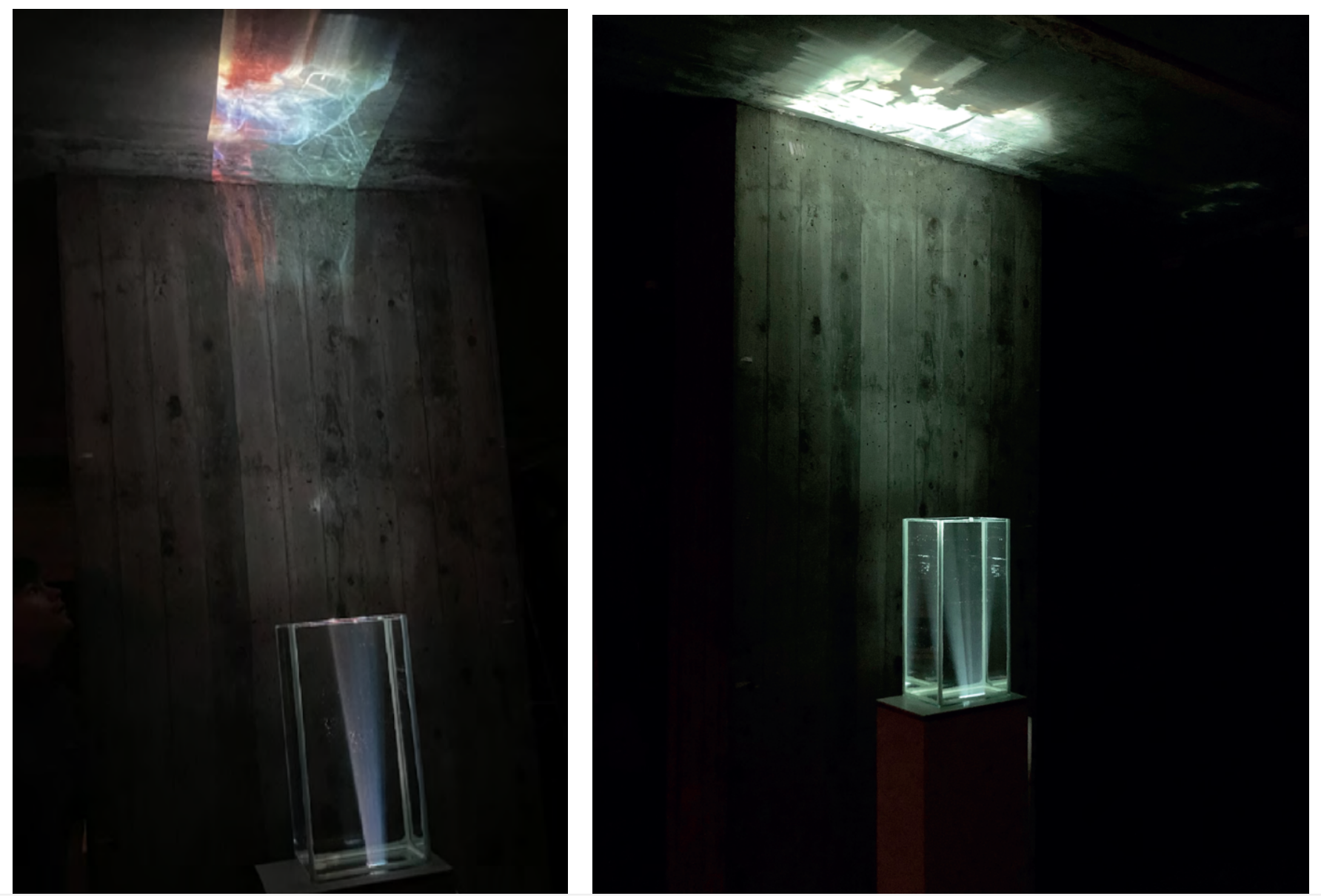

The Aquarium

At the start of the semester, I built a glass box—a tool that allowed me to break the surface and look beneath it. Through this aquarium, I observed the ocean in a different way, using it as a lens to explore underwater life. Everything I filmed through the aquarium is now projected, with the glass box serving as a way to interact with and engage the water. The aquarium offers a new kind of landscape— vertical rather than horizontal, more three-dimensional. Nothing in the ocean is fixed; it is constantly moving in all directions.

But despite this closer engagement, the sense of distance remained.

The Lens of the Anthropocene

In the anthropocene, the ocean reflects the consequences of our actions. Rising sea levels, plastic pollution, overfishing, and eutrophication— these aren’t abstract problems; they’re symptoms of a worldview that prioritises profit over sustainability. In his book “Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism“, sociologist Jason W. Moore argues that we aren’t just living in the anthropocene, but in the capitalocene— a world shaped by capitalism’s relentless demand for growth.

This perspective reduces the ocean to a value chain: fish are commodities, coastlines are real estate, and water is a resource to exploit. The current trajectory leads us toward the collapse of this system. Searching for narratives about how humans, within this capitalistic framework, can build or renew the connection between people and the ocean, I attended the “8th SIG Seaweed Conference” in Trondheim. Ambitious plans are being made for the future of seaweed farming with close ties to the salmon aquaculture industry, aiming to scale up production— perhaps an example of symbiosis?–I am not so sure.

The Painting

I’ve come to realize that building a relationship with the ocean isn’t about proximity; it’s about perspective. It’s about approaching it with humility, curiosity, and a willingness to listen. Art has always been my way of listening. Through painting, I’ve tried to capture the essence of my fascination with the ocean. Yet, no matter how much I create, the ocean always feels just beyond reach—an enigma I can never fully grasp. And perhaps that’s the point.

The ocean’s refusal to be defined is a reminder of its power. It teaches me that not everything in this world exists to be understood or controlled. Some things are simply meant to be experienced.

Conclusion: Shedding Skins

In the end, the ocean is not a landscape. It’s not a resource or a metaphor or a feeling. It’s all of these things and none of them— a paradox that challenges the way we think about the world. As I stare into the water, I’m struck by its ability to hold contradictions.

It’s vast and finite, inviting and unknowable. It asks us to shed our skins, to let go of our judgments and embrace its fluidity. And maybe, in doing so, we can learn to see the world—and ourselves—with new eyes.

Or to say it in the way of author John Green: I give the ocean four stars. It would’ve been five, but it refuses to give me answers.